This article originally appeared on Pola Weiß’s VRstories.blog where you can find the full version of it.

Finally, I can write about love — yes, love. My love for the Venice Film Festival and its fantastic VR section is boundless. This year, however, love plays a wholly different role… sit back, as today, we’ll be talking about Loveseat.

As the oldest of its kind worldwide, the Venice Film Festival (28.8.-7.9.2019) is just as venerable as it sounds; and even though virtual reality only joined the festivities in 2017, it is regarded as one of the best VR-centric exhibits.

The location: extravagant — the little island of Lazzaretto Vecchio, just outside of Venice, accessible only by boat. I think it quite fascinating of the La Biennale organization to place such a novel and innovative medium like VR on such an ancient island, of all places. In medieval times, victims of the plague came here to (more or less) wait for their demise.

And yet, there I am again this year.

The first visitors are already queuing for their morning cappuccino — some are fanning themselves, as it’s already quite warm here. The loudspeakers serenade us with Maria Callas, whisking a smile onto all faces in range. The coffee stand’s employees lilt along happily: “l’amour est un oiseau rebelle,” Carmen’s famous aria, they sing while buttering bread rolls and foaming milk.

L’amour, amore, love. This is also the centerpiece of a very unusual project celebrating its world premiere in Venice this year. Alas, aren’t we all on the lookout for the perfect partner? Unlike the times of Carmen and her Don José, who really weren’t made for each other, we can search for love in a multitude of ways today. Not just on Tinder, no, but in live shows.

‘Loveseat’ Embarks on the Search for Love

No sooner said than done. Outside, the sun scorches the parasols and the humidity forces us into a collective permanent sweat. I, however, find myself standing here in the cool interior of one of the installations, which have grown in size and ornament compared to the Venice VR of last year. In just a moment, I will witness a play that runs approximately 40 minutes.

The room’s mood is vibrating — everyone is strained in a positive way, a phenomenon I know too well from my visits to the theater. Three actors flurry about in the midst of the visitors, giving them friendly smiles and leading them to their seats.

On both sides of the long room, facing each other, are benches arranged on steps ample for about 50 people, a rectangular amphitheater. Large screens hang above on all four walls.

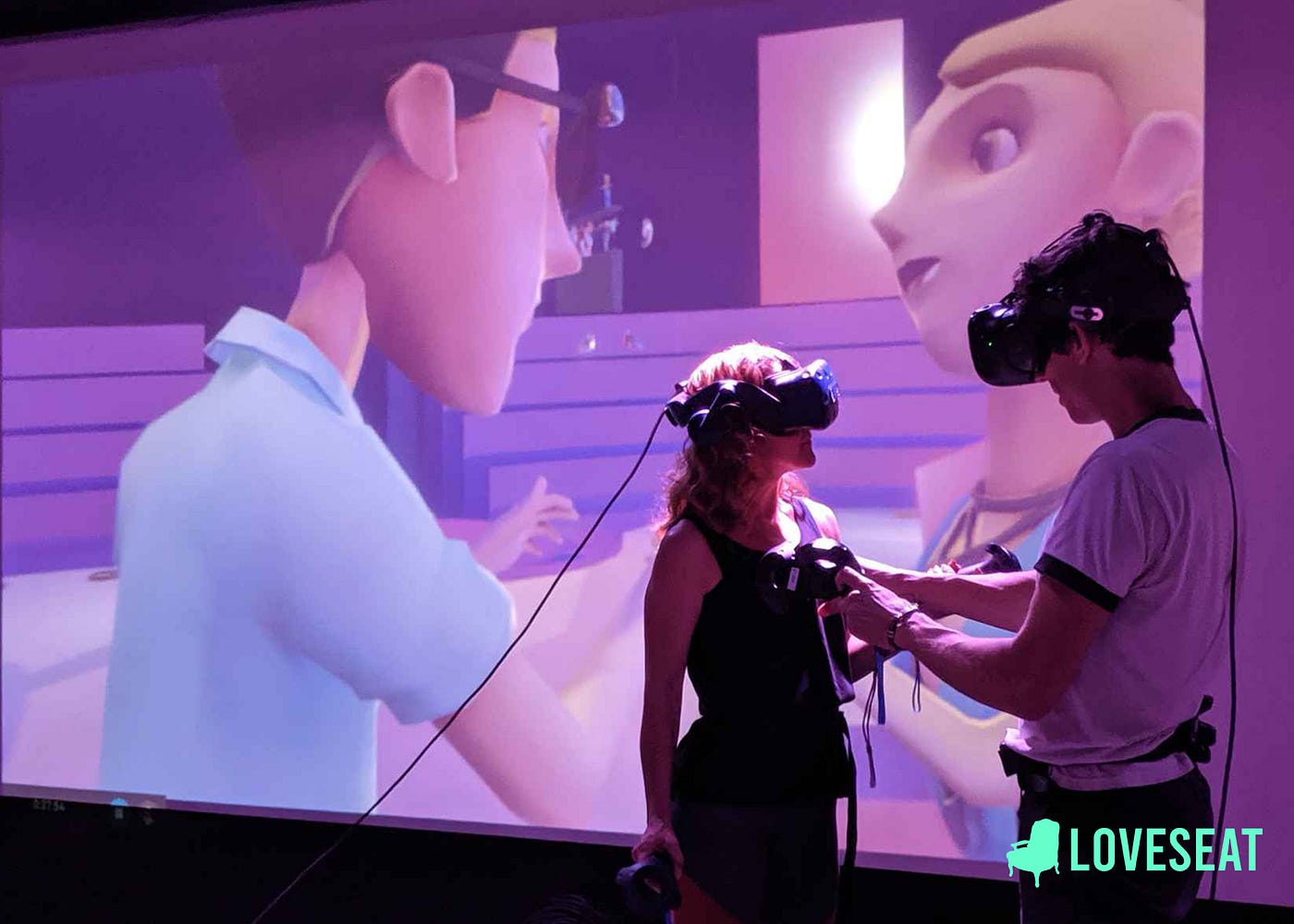

We will be seeing the performance twice today — at the same time. While we experience Loveseat in the real world in this room, it is also taking place in virtual reality in parallel. The screens serve to display the virtual performance.

The three actors step into the center of the room, wearing VR goggles on their heads and trackers on both feet and their hips. While they have already entered their colorful VR world, we watch them from our places. Then, the host (played by Sam Kebede) starts the show.

The Empty Seat

The two singles Abby (Jenn Harris) and Bruce (Jonathan David Martin) live right next to each other or at least their gardens border each other directly. Abby had renounced love once and for all, yet she lovingly cares for the colony of bees living in her garden. Nature must be allowed to sprout wildly and freely, she thinks, and so should her life.

Bruce is — what else? — the exact opposite. His garden has been trimmed to the last blade of grass, the tree is a meticulously pruned cube. Abby’s bees really upset him, as they keep buzzing into his so ordered world.

In the famous reality show The Perfect Partner (of which neither Abby nor Bruce have ever heard of), both of them will now have to court their perfect match. That match is — surprise, surprise! — not a person, but an empty chair. And yet, the chair looks quite different for both Abby and Bruce…

The chair as a symbol for loneliness, director Kiira Benzing later explains to me, is kept empty deliberately. This way, the audience can dabble with their own projections and imagine their own perfect match sitting in the chair. This idea has also made its way into an additional AR experience working only with sound and Bose’s audio sunglasses.

Two Plays for Two Audiences

Producing Loveseat was like staging two plays in parallel — in the “real” world and in a virtual world. On the one hand, it works very much like a traditional theater production: with costume designers, set designers and all the other established trades of the theater.

Get Pola Weiß’s stories in your inbox

Join Medium for free to get updates from this writer.

SubscribeSubscribe

On the other hand, there are the — as of yet — unexplored paths in VR. The team developed the stage for Loveseat specially via the social VR platform High Fidelity.

Special effects such as shrinking or flying they created themselves. The actors had to learn how to move with the VR goggles on their heads, the controllers in their hands, and the HTC Vive trackers on their bodies. While playing their roles, they also have to control objects in VR and react to the audience surrounding them in the real and virtual worlds.

Even the stage management system had to be refitted first. During the performance, the backstage resembles a newsroom: here, camera positions and image sections are chosen live and projected onto the screens in the stage room.

“Mac, We Can Fly!”

Every show in Venice features a team of thirteen people on location — including actors. Up to two team members are patched into VR from New York. Master of the spectacle: Kiira Benzing, whose last project Runnin’ was recently awarded best interactive experience by the Virtual Camera Jury at SXSW 2019.

An actress herself, Kiira Benzing hails from the world of theater. Having completed her schooling, which, among others, includes the renowned acting school LAMDA (the London Academy of Music & Dramatic Arts), she first turned to film as a director, however, and eventually founded Double Eye Studios. For Kiira, her work in virtual reality is just as much a return to the theater, she tells me in an interview during the festival.

Her love for theater becomes palpable in Loveseat. Moreover, the author of the play, Mac Rogers, is also a savant of the theater business. This does not just shine through in the form of humorous dialogs (“A beard? That’s not a beard, that’s a chin!”). He worked closely together with Kiira for the script, as she tells me:

I think that this production was particularly unique for him. He was involved with me telling him, ‘Mac, we can fly, we should have a flying scene.’ and ‘No problem, she can move an object easily because it’s weightless in VR.’ We have these opportunities to play with physics that we don’t have in the world in which we live. We might as well play with them, explore those things. So Mac and I worked through it. He asked me for a list of ideas and things that were really important to me to see reflected in the play. And he worked a number of those in. Then, as he did rewrites, we kept pushing things around and shifting it even further to heighten what’s capable of this VR medium.

Interplay Between Real and Virtual Worlds

It is exactly this exploration of possibilities that makes Loveseat so charming. Kiira Benzing and her team experiment freely, they juggle different genres and formats and stretch the boundaries of what is technically possible.

This experimentation is especially interesting for the audience in the real world. Not only does Abby start flying at one point, only to transform later on… At this point, I don’t want to disclose too much. This intersection of real and unreal is possible thanks to VR and the screens in the background of the actual stage that show what’s happening in the virtual world. There, the audience can follow a second play that adds a new dimension to what can be experienced onstage.

Naturally, this love of experimentation brings with it some inherent issues. While I was especially pleased by the scenes in which the VR equipment worn by the actors carried over as an analogy to their virtual avatar — for instance, when Abby shields her face from the bees with a hat and veil while watering her plants with the garden hose: in these moments, reality and virtuality melt into each other.

Other scenes, however, felt like they were missing essential theatrical elements. The intimate interaction between the actors onstage is sorely encumbered by the VR equipment. Kiira tells me they ran into similar difficulties in their virtual performance. When they first started, the whole thing felt like a production with puppets and masks, she says. Yet, by and by, they began to develop their own theatrical language:

My big concern originally — when I first started working with the platform High Fidelity and put actors into avatars — was: How could they get an honest connection to their scene partner if they can’t make eye contact, if they don’t have those tiny breaths of movement, if they can’t touch their partner. How do they actually exist in this world? That led to a study that we did for High Fidelity with some of my colleagues in New York: we began to explore what types of avatars might work for their bodies. And actually, they get a lot from each other; they don’t have perfect eye contact, they don’t have perfect lip sync, but they are finding ways to connect with each other emotionally and honestly.

A Prototype With Great Potential

In order to afford the audience this connection with the actors — and, in turn, to the story — on location, Abby and Bruce frequently remove their headsets. In those moments, the action onstage melds with the vivid and magical world on the screens in an enchanting manner. I would have loved to see more of such moments during the play.

This, however, only applies to the theater audience in reality: in VR, the avatars “freeze” for a couple of moments during these key moments. With one exception: at the end of the play — the real Abby removes her VR headset to hold an emotional monolog — the virtual Abby falls into an uncanny life of her own, repeating the same small gestures and lip movements, over and over. What could have been if the experiment were taken further, if the virtual Abby fully emancipated herself from the real person?

I saw Loveseat twice, once in Venice and once at home in virtual reality. At the moment, I think the play offers a more enticing experience for the audience on location. Thus, I believe the experiment still needs work to reach completion. More so, I see it as a first step, a prototype for a new and exciting form of theater that must be developed further — for both worlds.

I’m looking forward to seeing more experiments by Kiira Benzing and her team. So that they revolutionize the world of Social VR with their theater plays for good.

This article also appeared on VRstories.blog where you can find the full version of it.

Those of you who are interested in reading more about the experiments that finally led to Loveseat: follow the hashtag #AliveInPlasticland on Twitter.

Discussion