(The following contains moderate spoilers for La comédie virtuelle, Finding Pandora X, and The MetaMovie Presents: Alien Rescue.)

There’s a dancer looking right at the camera. Their face is pressed up close to the lens, taking up almost all of the frame. In a museum or film context, this would not seem quite as odd; but in virtual reality, to have it feel like the dancer is looking at us? That’s a feat. And to have three live video feeds coming to us from Australia, Switzerland, and India, in a 3D replica of a real-life theater venue, well, that feels like a magic trick. But the really impressive part is that I’m watching multiple clones of the same motion-captured dancers beamed in from across the world in a custom built space in a custom built app, with about a dozen other invited press and industry folks. We’re teleporting around the room to change our perspectives, sometimes flying up into the overhead catwalks of this digital theater space and back down, as the mocap-ed dancers do their thing for the next 20 minutes in La comédie virtuelle. And it’s all happening live for the Venice Film Festival, alongside two other live shows in VR, I’m told.

But try as I might, I can’t seem to tell if the dancers can actually see us, the audience. I never feel like one of them might make eye contact or acknowledge me by modifying their body movements against what my avatar is doing. The quick nod, the silent stare, the meaningful glance, or the mirroring of pose, these small acts are some of the things I treasure in live immersive work. But the more time I spend in virtual worlds, the more I realize that it isn’t always a given in virtual, remote immersive work. La comédie virtuelle is a cool experience that I’m glad I saw. I always enjoy seeing dance pieces in VR, but I struggle with the “live-ness” of the piece and how a maker can take advantage of the affordances of seeing and being seen in VR. And these issues are not unique to the piece I describe above; there are a whole host of other creators who are tackling similar challenges around live performances in VR, to varying levels of success.

Take Finding Pandora X by Double Eye Studios, which also showcased at Venice VR. In this interactive story, the previous Pandora has passed away and there is no new Pandora to take her place. Plus, no one can find the box of hope. To make matters even worse, most of the gods and goddesses have been locked out of Olympus (here, it’s a large custom-built world in VRChat) except for Zeus (Jonathan David Martin) and Hera (Pamela Winslow Kashani). Our host for the experience is Coryphaeus (Deirdre Lyons), or, just “Cory,” for short. She asks us, the audience, to be her Greek chorus. We are asked to change all of our avatars to the same gray ghostly figure and turn off various VRChat UI elements to help boost immersion during the show; we as the chorus are often conscripted to repeat whatever Cory says much like a real-life chorus, although there are significant lag/sync issues when all dozen or so of us try to talk at the same time. And an unseen voice keeps asking me to mute my microphone when I try to chant (my lack of headphones being a likely source of echo, whoops).

There’s a lot going on at once and it can be tough for those unfamiliar with video games or virtual reality to keep up with the performers as they pull us along the preset narrative. I notice a few folks in my group getting lost in the twists and turns of one the environments or their avatars oddly contorting when the participant inside is trying to sit and take a rest during the show, which can run up to 70 minutes long. And whenever one of the actors throws a question into the void, it usually takes a few beats for anybody in my group to unmute themselves and actually answer. Cory does her best to herd us along, but the mechanics of doing, well, anything in VRChat can stymie even the most skilled user. We’re obviously “on rails” in this story but the group is struggling to keep up.

Me, I find myself having a hard time connecting with the other actors, who seem to be always performing “at” us on a de facto stage as we form a semicircle around them, or trying to lead us to the right solutions to various puzzles. Zeus lacks any real chemistry with Hera and I don’t quite buy either of them as powerful gods despite Zeus’ grandstanding, gesticulating, or tossing of huge virtual props. At some point, the group is asked to split up on two separate quests with Zeus and Hera to find either the new Pandora or the box of hope. Sadly, few of the others choose to go with Zeus and have to be cajoled into doing so. Spoiler alert: both quests, inevitably, are unsatisfactory in their aims. But, never fear, there’s a big set piece scene that ties it all together with a tidy bow but relies upon participation from the audience. Surprise, hope was with us the whole time.

The other big live piece at Venice VR takes a completely different model of casting the audience. The MetaMovie Presents: Alien Rescue puts a single participant in the role of the “star” of an interactive VR experience. While the protagonist of the show is human scale and has a full size avatar, there are a number of silent spectators also along for the ride. They are embodied in the virtual space as “Eyebots”: flying metal cylinders that independently flit all around the main character as the adventure unfolds. They can run along ahead of you or drag behind you, but don’t really interact or contribute to the narrative. As for me, I eagerly accept the role of “hero,” curious to see what they’ve designed.

Before the start of the experience, I log in early to make sure that I’m ready to go as I’ve never used this particular social VR system before (MetaMovie uses the NeosVR platform). As the story starts, I steel myself and get ready to bring my A-game because there are a bunch of folks watching me and I really don’t want to let them down with a bad show. I feel intensely observed; it’s a bit uncomfortable at first, but I try to ignore the Eyebots. However, I quickly get the sense that I’m holding up the show with my bantering with my spaceship’s benevolent AI Ursula (Marinda Botha); she’s got a bunch of lines to deliver and we keep talking over each other, like a bad conference call. But soon enough, the computer tells me that my old pal Z (Nicole Rigo) has dumped a load of credits into my account in exchange for joining her on a mission: we’re to rescue a rare and dangerous creature called a “Zibanejor” from the secretive Kelosite Research Facility. Lucky me, I’m joining up with a ragtag gang of aliens who don’t exactly trust me.

Get Kathryn Yu’s stories in your inbox

Join Medium for free to get updates from this writer.

SubscribeSubscribe

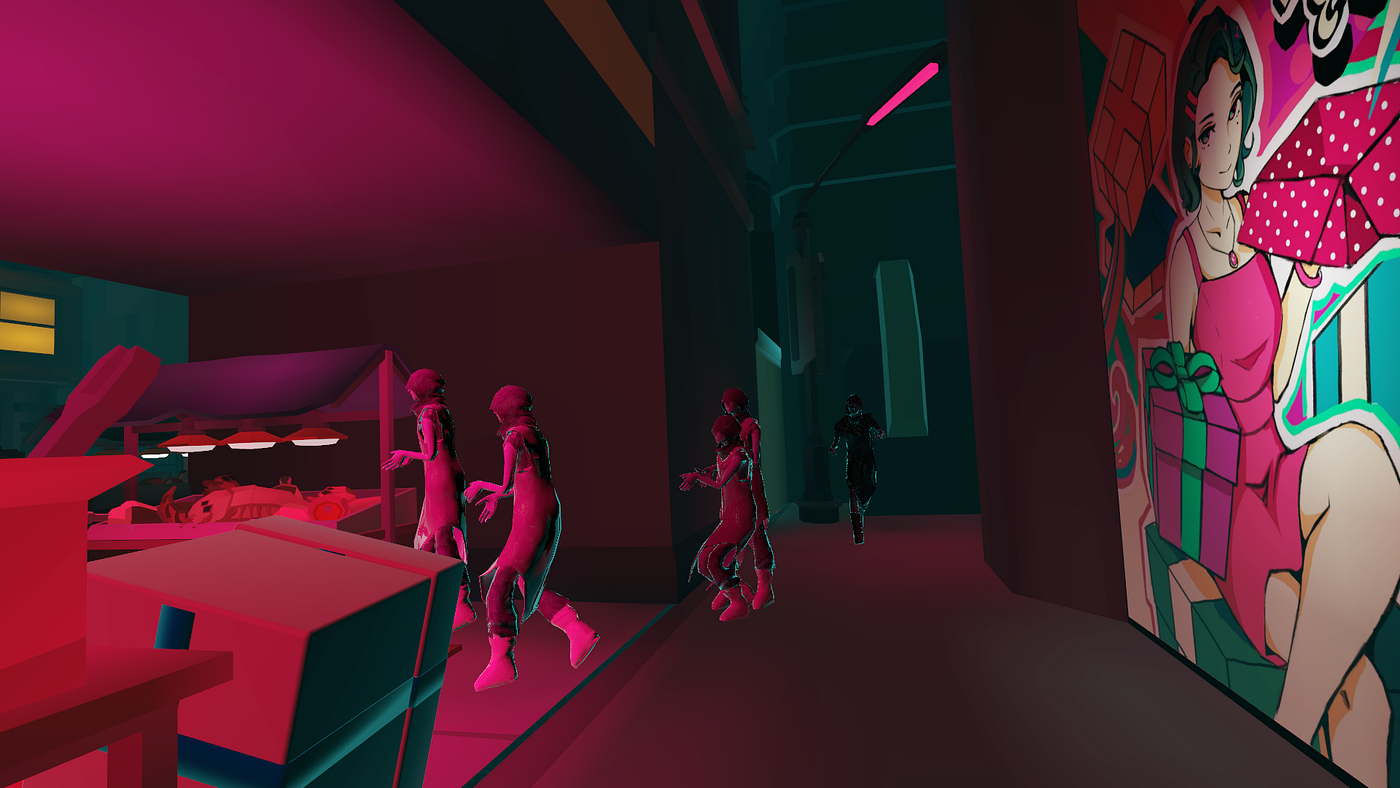

The world that the MetaMovie has built in service of this story is enormously detailed; we cover a ton of ground during the experience of Alien Rescue. It feels like we’re always on the move as characters frequently call out, “Kathryn, lead the way!” or “Yes, Kathryn, you should cover the rear!” as we go through unknown territory. There’s hardly enough time to catch my breath as we traverse long dark hallways, climb up through portholes, examine foreign computer consoles, and try to figure out what exactly is happening with this strange research facility. There’s something real bad happening here and we don’t like it, not one bit, and one of the members of the space gang also has a secret agenda. (Also: there seems to be a monster on the loose? Yikes.)

Still, I long for a pause button so that I can just stop and admire the world they’ve built. It’s hard to reconcile the epic level design with the fast pace of the story and I desperately need a breather. But the three actors keep calling my name, assigning me new tasks to do and asking me what I think of all this or if I’ve found anything interesting; of course, I’ve long forgotten their characters’ names (Baxter? or was it Axe?), but they all know mine. I start to wonder just how long and detailed their script must be and why they feel the need to constantly engage me. The situation hits differently when you subconsciously think of and treat your “NPC” like a real person. And I can’t just hit “X” for the next line of pre-written dialogue. I have to stop and actually think of a meaningful response when someone asks me a question, otherwise one of them asks if my mic may be malfunctioning.

Overall, I’m overwhelmed by the huge sets and constant stimulation in Alien Rescue. And partway through the experience, I start to feel the fatigue of being in a headset for so long. My experience ends up being 75 minutes in total, including tutorial time. And I’m a little nauseated by all the smooth locomotion in the world as teleportation isn’t an option for the hero just yet. So by the time we reach the inevitable conclusion of our story and the day is saved, just barely, by me somehow, I’m ready to toss the headset off and go outside for some fresh air. Personally, I know I’m a terrible shot, so there’s just no way I saved the team from whatever wanted to eat them. (It’s real tough being a hero, you know?)

In 2020, it feels like the age of ractors (the term for live human performers in VR from Neal Stephenson’s The Diamond Age) is finally upon us. In fact, for me, it has felt like the field has been quickly coming into focus over the last 6 months, via a transition that’s been accelerated by the pandemic. But it’s not as simple as throwing folks used to acting for the screen and stage into a digital space and letting them loose on VR users, or assuming that all of your participants are going to be fluent in the language of video games or new tech platforms.

Tender Claws and Adventure Lab (among countless others) had already been working on marrying live theatre with virtual reality in the Before Times; I am willing to bet that a large part of what makes these two companies particularly successful is their collaborations with creators like: experimental theatre troupe Piehole; or Jennine Willett, Co-Artistic Director of Third Rail Projects; or various members of the LA immersive theatre community, resulting in experiences with more room to simply “be” in the VR world. In these virtual worlds, there’s space for stillness as well as aimlessness as well as unstructured play, all in addition to the actor interactions and puzzles to solve. And, luckily, both companies have live experiences the public can currently purchase tickets to (Tempest, Dr. Crumb’s School for Disobedient Pets) instead of needing to attend an exclusive film festival like Venice, where these live shows were reserved exclusively for press and invited guests. I highly recommend you check both out if you have a VR headset at home.

And, so, at the end of the day, I find that the most challenging aspect of attending live performances in VR is also its biggest strength: a lack of definition and audience expectations. No one knows where this is going; of a thousand experiments, perhaps only a handful will work. We’re truly flying the plane as we’re building it.

It’s a brave new world.

And it certainly needs more creators like these in it.

Venice VR Expanded has concluded.

La comédie virtuelle (sans live performance) is available to the public through December 12; tickets are free but must be reserved. The MetaMovie Presents: Alien Rescue is expected to launch to the public in late 2020.

NoPro is a labor of love made possible by our generous Patreon backers. Join them today!

In addition to the No Proscenium web site, our podcast, and our newsletters, you can find NoPro on Twitter, Facebook, YouTube, Instagram, in the Facebook community Everything Immersive, and on our Slack forum.

Office facilities provided by Thymele Arts, in Los Angeles, CA.

Discussion