Jeb Havens answers audience questions about escape room design

During Escape Jam, attendees team up and design and test a 25-minute escape room, all in one day. Jeb Havens, the creator of Escape Jam, stopped by the No Proscenium Slack to answer some reader questions about what exactly “escape jams” are, the usefulness of playtesting, Tinder-themed escape room concepts, and more.

A transcript of Jeb’s Ask Me Anything answers can be found below; content has been edited for clarity.

If you’d like to join future NoPro AMA’s, join the NoPro Slack!

NoPro: For those who don’t know what a “jam” is, what is it in this context and where does the term come from?

Jeb Havens (JH): It comes from the term “game jam,” which is an event where a large group of people gathers for a day or weekend, split into teams, and create fully functioning games from scratch (traditionally video games, but sometimes board games).

‘Jam,’ obviously, references a jam session, where musicians gather to improvise and riff off each other’s energy to create something new and exciting. Ideally, by each bringing something unique to the table, the end result is something none of them could have produced on their own.

Tommy Honton: What made you want to turn the ‘jam’ model from video games to escape rooms? What were the biggest challenges of changing mediums from ‘digital’ to ‘non-digital’?

JH: I’ve been a professional video game designer, board game designer, and puzzle writer for many years. Throughout my career, my favorite experiences have been running “game jams” or design workshops and seeing the kind of magic that can happen when a group of people is given the space and time and direction to unleash their creativity.

Games of all types really lend themselves to the ‘iterative process,’ where you put something together quickly, test it out on a few people, learn, and repeat. The true magic of games happens when they are played, not when they are just a bunch of ideas in your head.

I think escape rooms are similar since so much of what makes an escape room great is the interaction between the players and the components and systems of the room.

Also, I just love escape games, and wanted to see the industry and the medium of immersive entertainment advance and push the boundaries and try something new. I saw that the iteration cycles were really slow, because it takes so much time and effort to open up a professional room (much of work unrelated to actual experience design). So, I wanted to create a space for designers and enthusiasts to try new ideas, iterate quickly, and get playful… without the stress of the business side of escape rooms.

Regarding the challenges of changing from digital to non-digital…. One big issue was simply finding the right space for the event since the physical space of a room can have such a big impact on the player’s experience. I’m very excited about the new space we found for this Sunday’s Jam (as well as future Jams), because it is such a quirky space, while still being a “blank canvas.”

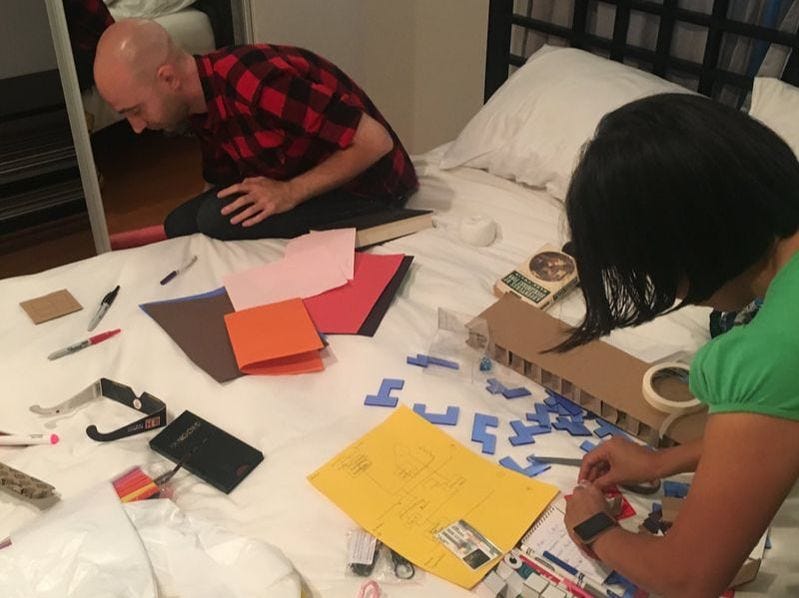

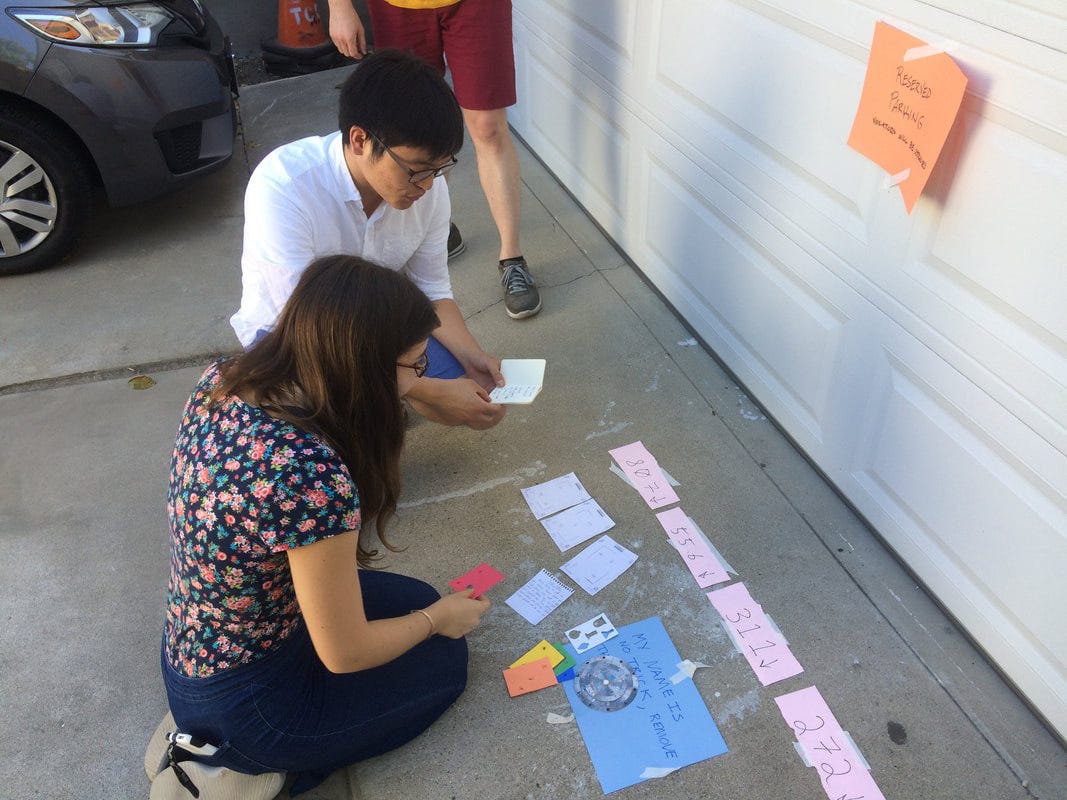

One of the benefits of non-digital is that it lowers the bar immediately for anyone to participate and test out their ideas. You don’t need special training to come up with a puzzle idea, and often you can build a passable prototype to test it out in a few minutes and some basic DIY materials.

Brian Postalian: As an escape room designer — where do you begin your design process? Narrative? Puzzles? Feel? Difficulty?

JH: Personally, I think it’s important to start by thinking about the overall player experience arc for the full game. In my workshops, I call this the ‘through line.’ Whether or not you are telling a particular narrative story, it’s important to think about the overall emotional journey of the player, and then keep that in mind as you design specific moments and puzzles to flesh it out.

I also like to map out (roughly) the main turning point moments for players. Often, these are either “Whoa!” moments, when the player encounters something that makes their view of the room expand and feel more complex, or “Aha!” moments, when the player puts things together, and the complexity suddenly decreases. The push and pull of those two forces create much of the emotional rollercoaster that great escape rooms have.

Kiara Vincent: What are some of the most challenging limitations of escape rooms, and how do you design around those limitations?

JH: One of the reasons I love escape games so much as a medium is because they feel much more limitless than other game media. For example, a video game or board game can much more easily keep the players within limits via specific rules and limited choices. The best escape games should feel like you, as the player, can do anything, and the world should respond appropriately. And it’s that player expectation that makes them especially challenging to design.

Since players can decide to do whatever they want, that makes playtesting and iterative design all the more important, so you can start to predict where players may ‘go off the rails.’ As a designer, you’re never going to be able to 100% predict all the crazy things players may try, so you have to focus on how to guide attention through cues and breadcrumbs you can leave them, so they know they are on the right path.

Much of this can be done with simple lighting or other effects, or by just making sure that at each moment in the progression of the game, there is something sufficiently more interesting than all the things you don’t want the player to be doing. Work on making the ‘right’ things stand out as ‘out-of-place’ or intriguing, or directly connected to something the player has just done, or some goal or question you’ve already put into their mind.

Kathryn Yu: What’s been the most surprising thing that you’ve learned along the way as an escape room designer?

JH: In general, I’ve learned that players almost never do what you first expect them to do. Hence, me being a broken record about “playtest, playtest, playtest.” And not only playtesting with you and friends, but playtesting with as wide a variety of strangers as you can. You will always learn something.

Another key thing that’s easy to forget is to regularly step back and put yourself in the mind of the player at various points of the escape. Make sure you know what you want them to be thinking. What objective is forefront in their mind? What is their current mental model of how each of the different components and systems in your room work? Like any good video game, from the very beginning, you want players to be bought into the drama and already thinking ahead about how they will succeed.

Kiara Vincent: In what ways are your personal room designs and the games created at the jams pushing the boundaries of immersive entertainment?

JH: The main thing I see at the Jams is people taking risks with new formats, subjects, and types of storytelling. Because people don’t have to worry about the business aspects or worry about their crazy idea failing, they can test out narratives that you’d never see in the current landscape.

Get No Proscenium’s stories in your inbox

Join Medium for free to get updates from this writer.

SubscribeSubscribe

For example, at the last Jam, one team created an escape game about trying to facilitate a successful Tinder hookup. Players were initially split into two groups, one trying to get into the car, find the location, and figure out where to park, and the other group trying to get the house cleaned up, light the candles, and remember the first name of the person coming over. It was completely crazy and ridiculous and is nothing like what you’d see in a current escape game business, but by attempting something so ambitious, we learned a ton about how one might push the boundaries in that direction (and also had a hilarious time doing it).

My hope is that as the Jams go on, new people and groups will bring new questions and challenge new assumptions about what escape rooms have to be. Ultimately, I do see a blurring of the lines between escape rooms and other immersive entertainment, so I’m excited about having a space where a lot of those lines can be safely and quickly explored to see what works and what doesn’t.

Ross Reilly: What element do you find most critical to the success of an escape room (success as defined by you)?

JH: Ultimately, it’s all about the player experience. Players should feel like they are pushed to their abilities, they should have a satisfying emotional roller-coaster, should end up feeling closer to their teammates, and should generally feel like human beings are awesome (themselves included).

In order for all that to happen, there are a lot of elements that need to fall into place, such as having a solid through line, well-balanced puzzles, opportunities for teamwork and specialization, and believable immersion. The best way to get there is through iteration and testing. In many years of designing games of all types, I still always find that my first ideas are never the great ones, but it’s in testing those ideas that I discover the truly great designs.

Strother Gaines: How do you set the line between ‘just difficult enough’ and ‘too difficult’ for your puzzles?

JH: When people talk about puzzles being ‘too difficult’ and thus not fun, it’s often because the player feels lost and frustrated, with no progress.

I think it’s possible to design extremely difficult puzzles that are very fun to solve, as long as they are designed such that the player is encouraged with smaller successes and milestones along the way.

For me, it’s less about difficulty and more about the player’s mental model of the system. If you see a player get stuck or frustrated, it’s usually because they aren’t able to form any workable model of the puzzle, and they don’t make progress and start to feel stupid. Perhaps that part of the puzzle is ambiguous, and the player tries several ‘guesses’ that turn out to be wrong. Or perhaps they are on the right track, but there’s nothing indicating that or encouraging them to keep going a little further.

There are specific kinds of playtesting and feedback that can help if a puzzle seems ‘too difficult.’ Stop the playtest-er at intervals and ask them to describe how they think the puzzle works, or what it is they are currently trying to do. If their mental model is off, you can work to add cues that help the player form the right mental model, or remove red herrings that are leading the wrong way. If their mental model is already close enough, then just add small sub-steps or rewards to let the player know that they are making progress, giving them the fuel to keep at it.

So, again, playtest and iterate. And remember that the goal shouldn’t be to make something difficult just for the sake of it, it’s to make it fun to solve by making it seem very difficult at first, then giving way to “aha!” moments and empowerment, as the player gradually figures out what’s going on.

Strother Gaines: Any puzzle types you just love to use? Conversely, any you think are tired, and you avoid?

JH: Personally, I love puzzles that rely on intuitive deductions: either from using an object or system in an unfamiliar (but intuitive) way or by combining elements of the narrative of the room itself. Those are the kind of ‘puzzles’ that feel the least like ‘puzzles,’ and instead just make the player feel really smart for putting pieces of information together the right way.

In general, I love puzzles that seem obvious in retrospect.

I also love anything that requires players to work together in unconventional ways, since this is such unique and satisfying aspect to doing an escape game with your friends.

I tend to dislike puzzles where the ‘difficulty’ partly lies in doing math problems. Any equations that would have me looking for a pen and paper annoy me. I also dislike when designers use ‘take the number of letters in the word,’ or other similarly non-intuitive ways to clue a combo lock.

The more that designers rely on the same old ‘conventions,’ and less on inventive new puzzle types which rely more directly on human intuition, the less we’ll be able to broaden the market for escape games to the general population, as opposed to just the group of enthusiasts who only would think to take the number of letters in the words because they’ve seen it used in a lot of other rooms they’ve done.

NoPro: How did you (specifically) end up organizing the Escape Jam?

JH: After many years of designing and analyzing games of all types (video games, board games, puzzles, apps, social games, escape games, challenges, etc.), I fell in love with escape rooms as an enthusiast, and knew that immersive entertainment felt like the future and where I wanted to be.

Also, one of the aspects of my career that’s always given me the most joy is running game design workshops, and watching people realize the amazing potential they have within to create new fun experiences for each other.

So, the idea of the Escape Jam was born. 🙂

I looked around online and saw that there wasn’t anything like it out there, so I decided to make it happen. In true ‘iterative design’ form, I started out small to test out the format and took what I learned from that to the next event.

And from here, it’s just about getting bigger and better, creating a space for the industry to experiment and play around with where this whole immersive entertainment thing is headed.

The next Escape Jam event will be in February 2018 in Los Angeles. You can sign up for Jeb’s mailing list find out more.

Join the NoPro Slack to be included in future AMA’s.

No Proscenium is a labor of love made possible by our generous Patreon backers: join them today!

In addition to the No Proscenium web site, our podcast, and our newsletters, you can find NoPro on Twitter, Facebook, YouTube, Instagram, in our Facebook community EverythingImmersive.com, and in our Slack community.

Discussion