The type of theatre that No Proscenium typically covers has shifted significantly over the last several weeks. Companies have closed in person experiences and quickly brought shows to previously underutilized platforms, standing up new concepts on Zoom, Google Hangouts, SMS, Discord, Slack, and more. These remote shows allow performers to work from their homes while also experimenting with different forms; these online experiences can also potentially reach audiences from around the world, including those who might not ever be able to attend in person.

But with this new virtual performance era comes significant changes in mindset. Just as radio stars struggled to adapt to moving pictures when they first arrived, and stage actors learned to approach television and film differently, immersive performers must do the same. Learning to perform to a muted or silent audience over telephone and web cam is no easy feat for folks used to leveraging a crowd’s energy when we’re all in the same room together.

To learn more about how creators are adapting, we spoke to several immersive performers about what they’ve learned thus far.

— Kathryn Yu, Executive Editor

A New Platform Calls for New Considerations

Creators should be wary of wholesale copying and pasting a physical theatrical experience into online channels warns Ricky Brigante of Pseudonym Productions (author of the 2020 Immersive Entertainment Industry Report). Whatever you’re making “has to be designed for the new interface, interactions, audience mentality, and more,” says Brigante.

Mitchell Cushman of Outside the March (The Ministry of Mundane Mysteries) agrees with this approach, stating that his company “have only been exploring work where the audience feels like an essential part of the experience — which has led us away from any kind of video streaming or recorded content.” Like many other immersive artists, Cushman tries to avoid work that creates “one way conversations” with a mass audience. Similarly, Daniele Bartolini of DopoLavoro Teatrale (Theatre On-Call) has learned to embrace these newfound limitations. He says: “Don’t pretend you’re in a theatre if you’re not. This work is very specific… [and] requires as much precision and attention as a show that unfolds in a site specific location.”

Jordan Chlapecka of Linked Dance Theatre, who are bringing a version of their immersive show Like Real People Do to the Internet, says their team’s design process starts with considering the audience’s previous experience with various platforms. He says, “people have different levels of experience (with the technology) as well as different levels of tech exhaustion.” So creators need to bear in mind that someone who spends all day in Zoom meetings or lectures may not want to partake in a Zoom theatre experience at the end of their work or school day. Brigante also advises being mindful of competing interests in people’s home environments such as the distractions of kids, pets, television, phone calls, food, alcohol, and video games.

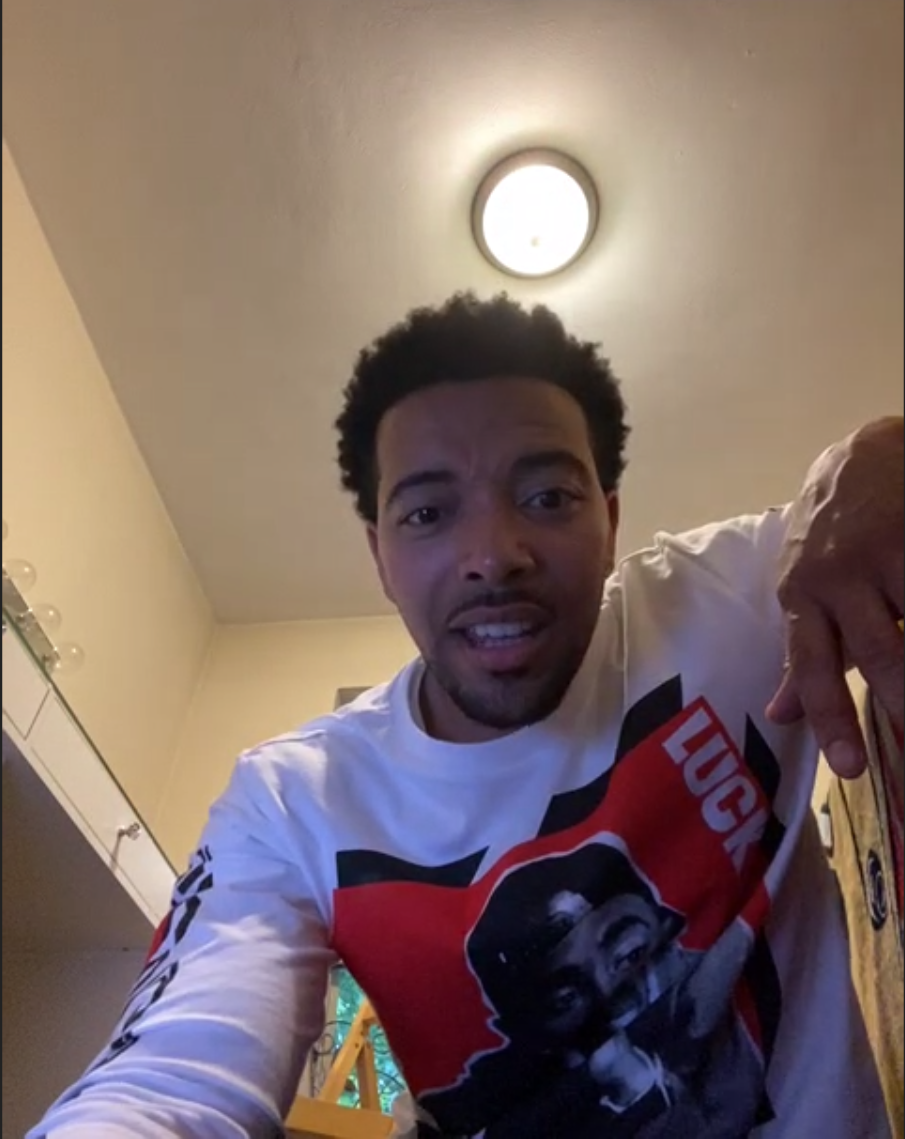

Actor Dexter McKinney, Jr. who performs as “Cupid” in the intimate Zoom show Long Distance Affair has observed similar distractions as well, saying “There is quite a stark contrast between face-to-face and remote performances.” He feels that “remote performances are such a new medium that we as performers and audience members have to get acclimated to it together,” emphasizing the collaborative process with the audience. McKinney also notes that audience members are often “so comfortable in their home that they aren’t necessarily on their best ‘in-public behavior’” when he reaches them during his one-on-ones.

An Era of Less Intimacy and More Intimacy At the Same Time

How are audiences reacting to these remote experiences and do they feel present in the show? Taking the temperature of a virtual room can be difficult, says Chaos Theory creator Jessica Creane. She observes, “Performers are used to reading the room at a glance. On Zoom, glances mean looking away from the camera, effectively breaking from the audience to see if they’re ‘with’ you. Being responsive to the moment becomes an act of prescience as much as presence.”

Please Don’t Touch (The Artist) creator Siobhan O’Loughlin also acknowledges the difficulty in discerning the crowd’s reaction; her team proactively encourages participants to watch the Zoom-based show using the “gallery view,” so that as many attendee faces can be seen on screen at once. The muted participants can also express their sentiment during the show on screen using upward or downward-facing jazz hands when prompted by O’Loughlin. PopUP Theatrics/Juggerknot Theatre Company does something similar in requiring all audience members to turn on their webcams during their remote experience Long Distance Affair, as well as encouraging everyone to unmute themselves during the show to actively participate.

Yannick Trapman-O’Brien (creator of The Telelibrary) has a slightly different set of challenges during his one-on-one telephone-based show which eschews webcams; he says he still feels a connection to each audience member but “the aperture is smaller.” It can also be difficult to gauge someone’s response to the material remotely, he adds.

“Sometimes I really have no idea how much it’s resonating, so it’s a very vulnerable act as well. You have to trust them to still be with you — and to reward and acknowledge that trust. We’re both working harder — and yet now more than ever it can’t feel like work,” he says.

Similarly, Chlapecka says their company Linked Dance Theatre will continue to emphasize “meeting people where they are at and where they are coming from” but when conducting experiences remotely, it “takes a little more work on the performers’ part to actually figure that piece out.”

And some performers have noticed that their experiences feel much more intimate these days than originally anticipated. McKinney attributes this to the fact that each one-on-one Zoom performance he does is “personalized for each guest, as we meet them in their space, on their device, at the time of their choosing.” Ángel Sánchez Perabá (performer in Long Distance Affair), has been surprised how deeply emotional his performances have been despite social distancing and a length of only ten minutes. “It’s really amazing,” he notes. And Rebecca Peyton (performer in Long Distance Affair), agrees. “Someone comes right into my bedroom and we are alone together,” she observes, calling the level of connection “extraordinary.”

Get Kathryn Yu’s stories in your inbox

Join Medium for free to get updates from this writer.

SubscribeSubscribe

But intimacy can come in many different forms, as O’Loughlin has learned, in her recurring Zoom-based Please Don’t Touch (The Artist) shows which can attract over 100 people. She uses a variety of tools in her performances, including running audience polls, soliciting ideas via the chat window, unmuting folks one at a time to weigh in with their opinions, as well as providing pre-written scripts for them to read as characters in her stories; this level of audience engagement often results in hours long “after parties” where participants can blow off steam and hang out more casually with each other.

Working Remotely Can Be A Glass Half Full

Creating an online immersive experience does also have some benefits, mentions Tessa Whitehead of Chorus Productions, the company behind the virtual Zoom nightclub Eschaton. Says Whitehead, “Most notably, we can put more of our budget toward hiring as many performers as possible since there are no real estate costs.” This has allowed the creators of Eschaton to have a cast of 24 people in separate Zoom breakout rooms scattered in various locations.

Brittany Blum, also of Chorus Productions, has found that they’ve actually expanded their potential audience during this crisis. “I think it’s safe to say that we’ve stumbled upon an extremely exciting new form of live entertainment…. We’re able to create more accessible high quality entertainment for audiences around the globe.”

Cushman echoes this point, noting that as a company, Outside the March has been able to perform their phone-based experience for people residing on every single continent except Antarctica, a feat that was “impossible to conceive of before the pandemic.”

Being Kind to Yourself (and Each Other)

Technical glitches are inevitable for many of these online platforms, no matter how much creators and their crews prepare, since much of what can go wrong is out of their control. Chlapecka of Linked Dance Theatre emphasizes the role of really understanding each individual platforms’ strengths and weaknesses, saying, “There is a large difference between Zoom/FaceTime/Google Hangouts, use those functions like you would a physical space, they can be very beneficial and actually guide your audience members.” He also adds, “I think now we are seeing that the body —especially when confined not only to a certain space but a certain platform—can sometimes react very differently than a body [which] occupies a real space. I think there is more to be mined on this as so much work is still to come, at least until we can get back into a physical space.”

Meanwhile, O’Loughlin says she’s learned to embrace any unexpected tech issues that may arise during her performances. “My patrons seem genuinely happy to be patient during the stalled moments — which have become part of the work itself — and it makes our togetherness feel even more authentic,” she states.

Performers working from home can also have their own unique challenges. Peyton of Long Distance Affair acknowledges the strangeness of collaborating remotely with team members who are often spread across countries and continents. “Performance is always a risk, but this jump is a whole lot further,” she says, describing the challenges of working with a remote director she’d never met in person to “gingerly feel our way in exchanging and critiquing” over Skype.

Additionally, Mitchell Cushman of Outside the March warns of fatigue setting in from hours-long Zoom calls with creative teams in preparation for remote shows, while performers like McKinney discuss the importance of maintaining pre-show rituals like the warmup. “It is sometimes easy to skip [it] as there are no other performers here with me, there is no theater to walk into or stage to walk on,” says McKinney. And while it may not be as evident to audience members who attend these shows virtually, the back of the house activities are just as complex for online shows “if not more important,” mentions Raylene Turner of DopoLavoro Teatrale.

Trusting the Process

Making work in this new era can be scary for creators as they venture into areas they haven’t played in before. Says O’Loughlin, “I am just as freaked out as I’ve always been to create work. The main trick is that I don’t let my fear stop me.”

Similarly, Trapman-O’Brien wasn’t sure his project The Telelibrary would turn out to be anything, saying that it began as “a rough playtest, really just trying to learn some basics in case other work came up…” However, the audience response was so strong that the project has “grown up into a proper part-time job, and the most exciting thing I’m doing,” he says. He advises other immersive creators to “be okay with making something you don’t recognize or understand yet.”

Creane says that performing remotely actually feels normal to her during this time, stating, “Performing has never been about being on a stage; it’s been a way to meaningfully connect a group of strangers and collectively share in a story that affects all of us. That much hasn’t changed at all. That mission lives on.” O’Loughlin echoes this point, emphasizing the necessity of the audience. She also adds, “The only way to experiment in immersive is with other human beings.”

There can be other similarities between creating in-person or remote immersive work. Whitehead notes that regardless of what they’re making, “…like any show, the richer, more in-depth narrative work we do, the more engaged they are.” And at the end of the day, despite the struggles, remote performance can greatly enrich the lives of both the creators and attendees, says Peyton. “I am astonished [at] how important not only the [performance] is, but this virtual being together, to be reminded that we are social animals and that we are all going along in our silos, but at the same time and with similar hopes and fears,” she muses. Creane agrees, reminding us that human connection remains the goal:

“Remember why you’re doing this: to create spaces of joy and intimacy that help us get through moments of fear and uncertainty together,” she says.

Find interactive and immersive experiences you can attend from home on our Now Playing: Immersive for ‘Indoor Kids’ page.

NoPro is a labor of love made possible by our generous Patreon backers. Join them today!

In addition to the No Proscenium web site, our podcast, and our newsletters, you can find NoPro on Twitter, Facebook, YouTube, Instagram, in the Facebook community Everything Immersive, and on our Slack forum.

Office facilities provided by Thymele Arts, in Los Angeles, CA.

Discussion